We All Take from the River

We All Take from the River

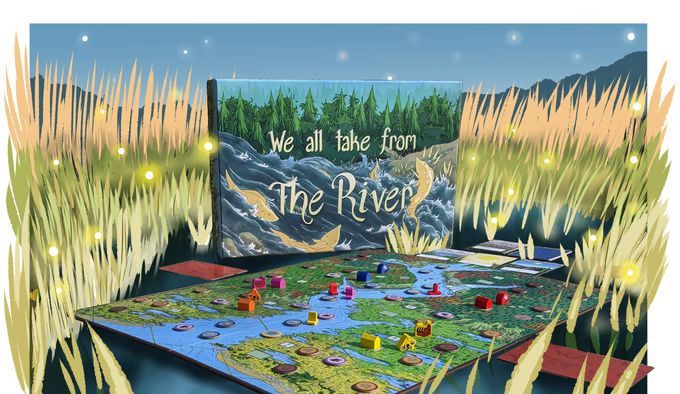

A board game with a meaningful message

Hey, fellow adventurers of the tabletop realm! Today, we embark on a journey down the winding paths of environmental stewardship and strategic gameplay with the new board game, “We All Take from the River” by Ben Hammer.

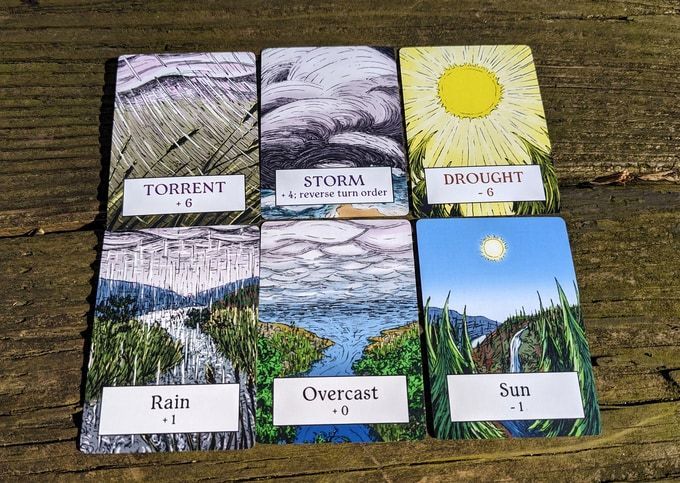

This game invites players to step into the shoes of different communities, each with their own visions for the future. As you navigate the twists and turns of the river, you must gather resources, adapt to changing weather conditions and balance your goals with your neighbors’. You will encounter challenges and opportunities that mirror the complexities of real-world issues, from forestry management to wetlands conservation. “We All Take from the River” offers a truly immersive experience that educates, entertains and empowers players to make a difference.

We’re really excited that someone is taking the time to recognize deep-rooted issues with our rivers these days and making people aware that every decision can have pros and cons. We’d like you to get to know the game creator, Ben, and his motivation for changing the world, one game at a time.

Welcome, Ben! Thank you for talking to us about your exciting board game project, “We All Take from the River.” Let’s dive right in! First of all, congratulations! Can you tell us a bit more about what inspired you to develop “We All Take from the River”?

Ben: Thank you! It’s been really wonderful to see so much interest in this passion project of mine.

I was first inspired to make a game that mimicked policy and community decision-making that happens in real life. Basically, I wanted a game where players weren’t necessarily on the same team or opposing teams but instead had a chance to decide their relationships for themselves. They would have their own goals, which might overlap or might not, and would have to work out for themselves how to manage a shared space.

Life along a river immediately stood out to me as a perfect setting for such a game because the impact of the actions of one individual or group is so clear. If I pollute upstream from where you live, you have to reckon with the direct consequences of my actions, not me. So players are forced into conversations about land management, water use, conservation and all kinds of other interesting topics.

The game seems to offer a unique blend of environmental education and strategic gameplay. Can you explain this a little more, specifically some interesting things people can learn about their rivers?

Ben: Absolutely. The most important part of designing the river environment of “We All Take from the River” was to capture how our impact on the environment ultimately has human consequences. Players can cut down all the trees to build up their industry, but that will increase the risk of floods when the forest is not there to protect them. If they overfish, there won’t be any fish left to reproduce. If they pollute, that pollution will get in the way later on.

All of these relationships between the players and the river exist in reality to some degree. Players learn a bit about the kinds of decisions that go into environmental management and sustainability as they come up with their strategies for winning the game. An important point to me about this was “show, don’t tell.” The game doesn’t tell you about the risks of your actions; it lets you see for yourself.

The game features a variety of roles, each with its own objectives and strategies. Can you tell us more about how players navigate these roles and the potential conflicts that arise?

Ben: Each player has two objectives that must be accomplished for that player to win. Say you and I both want to build a city. We can work together on that because our interests are aligned. But then if my other objective is to clean pollution out of the river and yours is to stockpile fish, we might find that difference creates conflict. Maybe the way you gather fish will create pollution, which is a problem for me. Alternatively, if we both want to stockpile fish, we might run into a scarcity problem when there aren’t enough fish available for the two of us. In that case, we could be in direct competition.

An important point is that we don’t know what each other’s objectives are. Like in real life, we can only interpret one another’s behavior and talk to each other to try to figure out where we stand. If one of us is lying, that could cause more tension. Maybe I promise you I won’t fish in your part of the river, but at the last minute, I betray that trust and do it anyway.

The game also offers solo and two-player modes, which is quite intriguing. How does this work?

Ben: The solo and two-player modes change the dynamic from being about diplomacy to being purely about sustainability. In these versions of the game, you, and possibly a partner, want to stockpile fish, build a city and do it without leaving any pollution behind. So you have to develop your industry in a way that is harmonious with the environment you live in. You must deal with the consequences of your own actions rather than letting those actions become someone else’s problem. In practice, this makes for a much more puzzly type of game.

It’s impressive to see your dedication to sustainability not only reflected in the game’s themes but also in its production. Can you tell us more about your environmental commitments and the steps you’ve taken to minimize the game’s ecological footprint?

Ben: It is hard to make an environmentally friendly board game, but I’m doing my best. The Forest Stewardship Council approves all of the paper and wooden materials to avoid contributing to deforestation. I am also minimizing the use of plastic in the game. Ideally, the final product will not use any plastic at all. Hopefully, we’ll end up with a product that lasts a long time, is produced sustainably and can be recycled at the end of its life.

What’s your end goal for this game?

Ben: Gosh! That’s a hard question. I would just like to see this game out in the world. If people can play it and enjoy it, then I’ll be happy. I would also really love to see it used as a teaching tool, and maybe even inspire other games to balance education with fun. That, to me, is an important point. A game can’t really be educational if it isn’t fun because if it can’t hold the player’s interest, then they aren’t going to learn anything from it. I hope I’ve made a game that is fun first and foremost but also makes people think.

Lastly, before we wrap up, what do you love most about rivers?

Ben: Looking at them! I don’t know about you, but when I was a kid and it rained, I would always run to the nearest trickle of water. I’d pile up sticks and rocks to make dams, bends and rapids, and then just watch the water flow. There’s something so captivating about flowing water.

I grew up hiking through the Appalachians and Shenandoah Valley. I have a particular affinity for Catoctin Mountain, which is in western Maryland along the Appalachian range and whose streams flow down to become part of the Potomac. I would hike from there to Harpers Ferry, where the Shenandoah and Potomac meet. I’d follow the little streams to the river and watch them become whitewater rapids. It was an important, magical part of my life.

Thank you so much, Ben, for sharing with us today. “We All Take from the River” sounds like an incredible board game with a meaningful message. We’re so excited to check it out and share one with a lucky member of the Forever Our Rivers family. We wish you the best of luck and look forward to seeing the game come to fruition.

Ben: No, thank you! I think Forever Our Rivers is doing some really wonderful and important work. I love that I can be a part of it any way I can.